POSTED October, 2013

Story by Petty Officer 3rd Class Blaine Meserve-Nibley

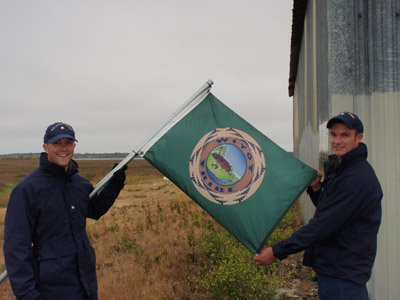

National Strike Force

Pacific Strike Team

The Wiyot Tribe was celebrating their annual World Renewal Ceremony on their most revered land when tragedy struck. Men of the tribe returned from collecting supplies for the sacred gathering to find women and children slain by settlers. The 1860 massacre occurred on their most sacred land, Indian Island, which was believed to be the center of the universe.

In 2000, 140 years later, the Wiyot purchased the site in hopes of continuing the sacred use of the land. All that was left were remnants of an old ship repair facility, which used rails to haul vessels onto the island for application of paints and wood preservatives. In March 2013, the Environmental Protection Agency declared Indian Island a Superfund site under the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act due to the lead and chemical preservatives deposited by the shipyard.

Due to the sensitive historical significance of the land, it was decided that capping the contaminated area with rock and soil was the best course of remediation. The EPA requested the assistance of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Pacific Strike Team for site safety supervision, particularly in the waterfront operations. Initial response by the Pacific Strike Team consisted of a response supervisor, response technician, and response member, to oversee operations for the EPA’s On-Scene Coordinator, Chris Weden.

“The Wiyot Tribe had exhausted all avenues of funding to renew their sacred ground on Indian Island. All that remained was the installation of a permeable cap atop the shell mound to prevent direct contact with the contaminated soil,” said Weden. “Capping was the only viable alternative that would achieve renewal of this sacred ground and preserve the historical and culturally sensitive setting.”

Getting the supplies to Indian Island for continued site removal actions and operations required a conveyor belt loader, barge, and heavy machinery for offloading cargo. With the complexity of operations, Strike Team responders split work into two operational components, barge operations and site removal actions.

“The logistics of the site were particularly difficult,” said Petty Officer 1st Class Karen Sinkey, the response supervisor for the case. “We had to work with the tides to get our supplies onto the island which created large amounts of work in a relatively short amount of time.”

The site also required the demolition of a small house which underwent asbestos abatement within the first week of site operations. Human remains and artifacts dating back to 900 AD were expected to be under the foundation of the house due to the natural decay of the island.

Chief Petty Officer Cody Staneart, a response technician with the Pacific Strike Team, worked closely with tribal representatives while the structure was torn down. He reiterated the importance for the Wiyot tribe to recover and preserve any remains and artifacts found on the island.

Completion of Indian Island’s site removal actions has been accomplished safely and efficiently. Stephen Coleman, the tribal representative and environmental director for the Wiyot, expressed excitement and optimism for the sacred grounds. During one of Coleman’s visits to the site, he said, “we are excited to see the completion of this project and are thankful for all the work by the EPA.”

In February of 2014, Indian Island will be closer to its original state, before the tragic massacre of 1860. The site’s restoration will be just in time to complete the Wiyot’s World Renewal Ceremony. This will not be just any annual ceremony for them though; they will be completing a ritual, cut short by death and betrayal, more than 150 years ago, bringing closure to Indian Island, and the Wiyot Tribe.